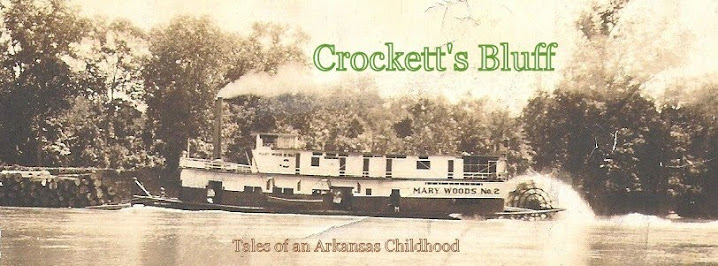

Fanny and Charles Dodson at their home near Crocketts Bluff

Fanny and Charles Dodson at their home near Crocketts Bluff

Summer 1968 Bluff during my early years was in every traditional respect a segregated southern society from the mid-nineteen thirties until the decade immediately following the aftermath of the

Brown vs Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court in 1954, and there certainly were over those years incidents of overt and violent, as well as covert and indirect, acts of racial oppression of its Black members. Acts of this sort to which I was witness remain etched in my memory today, sixty or more years later. One would like to believe, however, the Bluff was throughout those years a more open and just and generous community than many of those that populated the states of the deepest South.

In fact, among its most noble and respected families -- names like Allen, Phillips, and Dodson come immediately to mind -- were families we would label today as African-American, but who were distinguished in those days from their white neighbors not simply by their skin color but their reputation and example as responsible workers, individuals of integrity, faithful neighbors, and devoted parents.

"Charlie" and Fanny Dodson, pictured above, are noteworthy to me, not only for the qualities I've noted, but also for the fact that somehow they sent their four children to college even before the

Woodiel family began to make it a tradition.

One has to meditate on that fact for a while to fully appreciate its significance.

Two Dodson Stories

One

From "Miss" Fanny

During one of the summers between my college years at Arkansas Tech I managed to get a job once held by my father S.A. with the AAA. My task was to go from farm to farm and determine by means of large aerial photographs whether individual farmers had exceeded their

allotted acreage.

It was during one of these visits that I found myself chatting with "Miss" Fanny [same old tradition: I called her "Miss" Fanny and she called me "Mr." Dale] while waiting for Charlie to come up to the house from the cotton field below the hill on which it sat. I can't recall what brought it on, but I believe it was one of those very large cast iron cauldrons used for a variety of tasks including washing clothes before the advent of washing machines.

I can hear her voice in my memory, but I'll not attempt the dialect, though the story is better with it. So I suppose that will remain special just to me. Nevertheless, she told me a story about the day just before "my last baby was born."

She had "been

choppin cotton all

mawnin" and had decided just before noon to come up to the house to make some lunch, or "

denna," and had decided, while the lunch was cooking, to go down and "start a bit of wash" by building a fire under the large cauldron. At this point in the story, pausing while turning to look back down the hill, she slowly reflected:

"And, you know,

Mista Dale,"when I cum back up that hill, I

wus a

carrin that baby in my arms!"

One

About Mr. Charlie

Some time later that same summer I was in

DeWitt on one of those sweltering Saturdays of July when lots of folks have come to town. Like many other

predominantly white folks -- I had made my way to

Coker-Hampton's Drug Store since it was the only -- or certainly one of the very few -- establishments with what amounted to an air conditioned atmosphere.

Am I'm sitting at the soda fountain counter, I'm suddenly aware of a disruption behind me just inside the entrance, and I turn to find the black man lying apparently unconscious on the floor is Charlie. I rush to where he's lying just as one of the Hampton crew has arrived from somewhere in the back. (There is general muttering from customers and other observers as the spectacle proceeds. The phrase "drunk nigger" sticks in my mind.)

"Do you know this man"? blurts the Hampton pharmacist.

"Yes, I do, his name is Charlie Dodson."

"Well, could you help get him out of here? Dr.

Rascoe's office is just around the corner."

By this time Charlie is awake and totally startled. Perhaps he realizes he's just fainted, but he's glad to see my face, I can tell. I help him to his feet and out the door. I put his arm around my neck and my arm around his waist, but after a few strides he's able to manage on his own.

We make our way around the corner and up the long flight of stairs to the doctor's office. The

receptionist is startled, and she immediately interrupts Dr. Roscoe who is with another patient. He comes forth and with an immediate smile:

"Charlie, what on earth's the matter?"

For me, it was one of those rare moments of complete satisfaction.

Charlie Dodson is all right, and so am I. He's not a young man and he has just suffered the shock of coming from a sweltering temperature into an unreal rush of cold air. And what a relief for us both to learn even the county doctor knows and respects Charlie Dodson.

Of course.