Here are two childhood memories written for my grandson Griffin Bliss for a project related to Lois Lowry's novel The Giver in his seventh grade English class at St. Andrews School at Savannah, Georgia.

The first is about my first job at about his age plowing cotton for Mr. George Kline in his field out the Hill Road just west of Voss Lake. The second is a recollection of the recurrent thrill of all Bluff children at the sound of the whistle of the Mary Woods No. 2

About Your Age

When I was about your age, a sixth or seventh grader, I was

offered my first real paying job.

Something more than the familiar string of unpaid chores assigned to all

boys that age who lived on farms in rural Arkansas in the late 1940s.

It was a relatively simple job working on a small cotton

farm owned by Mr. George Kline, one of our neighbors in Crockett’s Bluff, a

small community at the bend of the White River where I was born and grew up.

The downside of this job was that I was required to be at

his house shortly after sunrise in the morning, not to return until the sun was

setting in the evening, a long day. But

the upside was that I was paid what was to me a hefty sum of $2.50 per day.

Since the field where we worked was almost two miles from

his house, we rode the horses back and forth each day we would be using in our

labors.

I was required simply

to stabilize a plow, pulled by a great buckskin horse appropriately named

“Buck,” up and down between the rows of cotton plants uprooting any grass or

weeds that might be there. Mr. Kline

came along behind me down these rows with another smaller and more precise plow

– pulled by his favorite horse “Lightning” -- that loosened the soil and “cultivated”

the plants in their early stages of growth.

Buck was an enormous so-called “draft”

horse, bred for hard and heavy work, and his strength appeared to me to be

unlimited. So, any thought that I, at

less than a hundred pounds, was supposed to control his starting, turning, and

stopping movements with the reins I leaned into from time to time tied behind

my back, was a joke. Consequently, Buck

stopped and turned whenever he pleased, much to my enormous frustration.

Consequently, since I never gave up trying to control him,

from time to time over those sweltering summer days I suffered the modest shame

and embarrassment of being gently chastised by Mr. Kline about the quality of

the language I addressed to poor old Buck.

It was a long summer and the work was hard and long and

generally hot. But it was work of the

sort one got paid for, and I spent the first twelve dollars I earned on a used

red bike with characteristic balloon tires at the Western Auto Store in DeWitt,

the county seat of Arkansas County Arkansas.

As I rode it for

miles over the graveled roads leading in and out of Crockett’s Bluff I felt

–what with a paying job – a new sense of what I would now call liberation.

*********

|

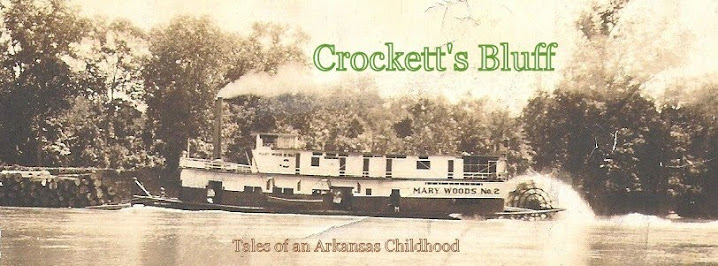

| The image of an unknown photographer from a Woodiel family album and title image for this site. |

The

Mary Woods No. 2

The photograph of the

paddle-wheel steamboat pictured above was made from the bank of the White River

no more than two hundred yards or so from where I was born in Crockett’s

Bluff, Arkansas, a village in the 1930s

much smaller and even more “quiet” and “tired” than the Macomb that Harper Lee

describes in To Kill a Mockingbird.

So, when the steam-whistle of the Mary Woods No. 2 was

sounded, everyone, particularly children, dropped everything and headed for the

bluff banks overlooking the river.

Its sound could be

heard long before its barge of logs nosed slowly around the bend beneath the

red clay bluffs for which the village was named. We knew we were in for a treat, something truly

awesome to us. She was majestic: grand

and powerful enough to move upstream a barge stacked with logs larger than

anyone ever viewed elsewhere. And she

made all the noise necessary to justify her presence, the sound of her engines,

the splashing patter of her enormous rear wheel, and the

usual additional whistle as a special treat to us from the pilot on the bridge

who always returned our waves.

The experience was necessarily brief, since even though she

moved slowly when compared with the familiar out-board powered fishing boats, a

full view was limited to a panoramic minute or two, so it was necessary to run

barefoot down along the bank for the next clear opening with a view.

Then, when she was gone from view and rounding the next bend

near the familiar sandbar, her super gigantic waves having reached the shore

making the house boats bounce like buoys, we were left with the image above,

the Mary Woods with the steam from its twin stacks streaming along its back

downstream as it forged upriver its massive barge of freshly cut timber.

A scene that is in memory almost as alive now as it was then

– a lingering sensual feast in the midst of an otherwise long, slow and quiet summer day in a “tired” little

hamlet at the bend of the White River.

|

| At the viewing site with my sister Maureen Shireman. |