According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture, folks in Arkansas have the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto to thank for bringing swine to Arkansas in 1541. Their offspring remain throughout the state today. While in the 1930s they served, in both their wild and domesticated varieties, as a welcomed source of protein for folks in Crockett's Bluff, today they have in their feral form become a statewide nuisance and enemy of the general natural environment.

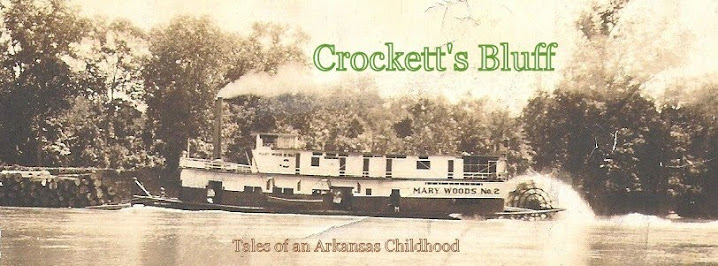

Among several rare photographs passed along to me some time ago by Hallie Keithley - still to this date the oldest current resident of the Bluff - reflect life in the 1930s generally and more specifically life on the River.

The image below is especially rare and historically interesting for both the subjects in the fore and background. Thanks to the notes neatly inscribed on the back of the picture by Flavelia (Bela) Kline, both the husband of one of the figures in what appears to be a make-shift barge and for most of the years of my youth the post mistress from a room in the Kline house.

George and John Kline are returning from the final day of the wild hog roundup in 1931: "Geo and John Kline leaving Monroe Co. on the last day of the hog round up, Jan. 15, 1931. The Steamer Robert H. Romander(?) coming up the river with 2 barges of logs 200,000 ft. It took her 15 min to make Crockett's Bluff Bend in White River."

|

| The Kline Brothers |

|

| Charlie McDonald's House Boat |

|

| CC:Riley Pool, Geo. Kline, Emmet Yokem, Chas. McDonald and ? |